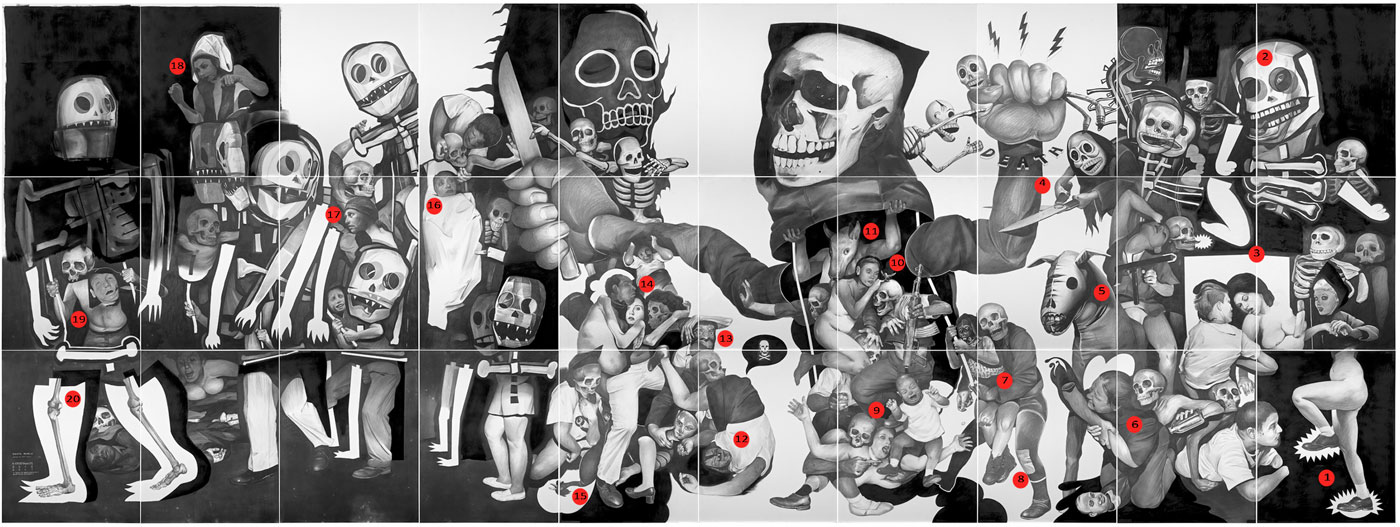

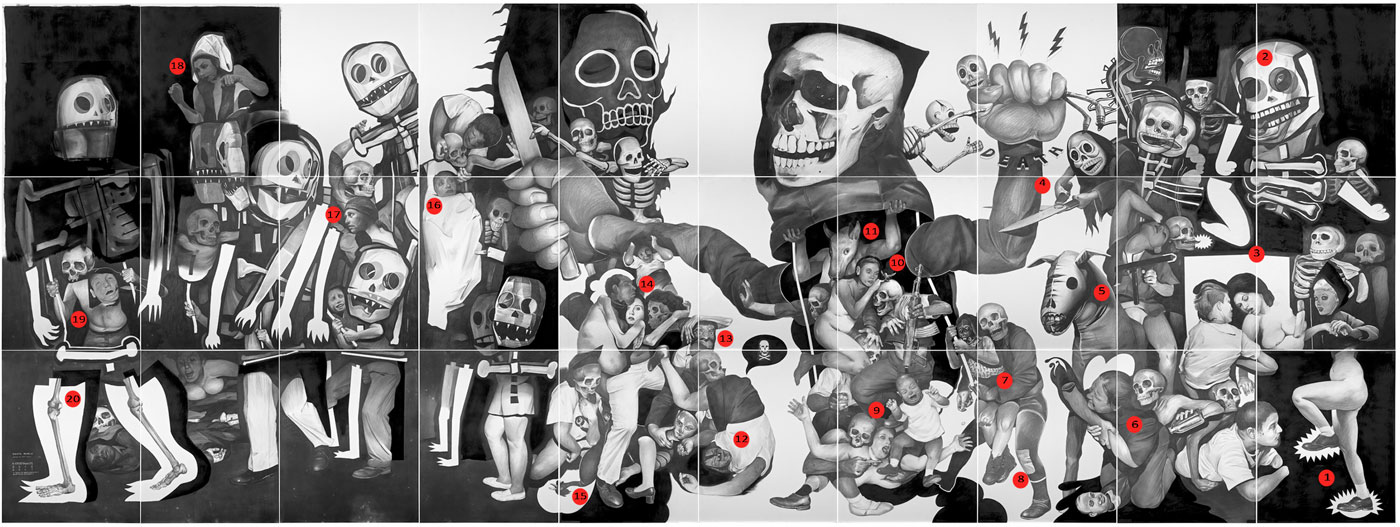

back to Morbid Curiosity exhibition pages

Death March Imagery Guide

Hugo Crosthwaite’s Death March is spatially and ideologically divided in a manner reminiscent of James Ensor’s Skeletons Fighting Over Body of a Hanged Man (1891). The composition is anchored by two primary embodiments of death: on the right is the masculine death figure that represents death through war, a man’s game, and the left deals with a feminine death as it is encompassed by the mother of death – a madre figure who is responsible for creating and nurturing life.

The numbered dots on the image correspond with the numbered list below:

- This pair of legs initiates the Death March. We are nude and vulnerable when we enterthe world, and we immediately begin our march towards death from the moment we are born. The flash bubbles around the feet indicate that we come into life with a big bang, our feet firmly planted into the earth.

- Religion and superstition are used to ward off death, but beneath the physical display of these superstitions is a doubtful human, an eye peering through the false idol. The eye realizes the inevitability of death and questions the validity of these life-preserving rituals.

- The blocked white area represents a television screen. The female figure in it is playing

dead, symbolizing fake deaths as seen in films and on T.V. However, the man beside her

is actually dead, symbolizing death as presented by the media and in the news. Both

show how the television desensitizes the public to the subject of death, and how hard it

can be to tell the difference between reality and fantasy.

- Death tries to prevent itself from happening as it attempts to save a figure from the fist

of death by cutting the perpetrator’s arm with giant sheers.

- A reference to Jeff Koon’s mylar balloon animals, this horse mimics the heroic war

portraits of famous generals. However, a female, an anti-heroine, rides atop holding a

gun that is pointed away. Beside her is a skull sticking its tongue out in self-mockery.

- Beneath the steed is a mourning woman who clings onto a broken, empty arm. Like the

empty vessel that the skeleton beside her is draining, there is nothing left of this life that

she is hanging on to. Death encourages her to let go, for if one mourns too long they

become one with the deceased.

- The nails and screws on Christ’s stomach allude to the Kongo nail fetish, in which

protective sculptures tacked with nails are meant to ward off evil, offer protection, and

settle disagreements. In this juxtaposition of Christian and pagan symbolism, the Christ

figure is “hammering” out a deal with death.

- A death figure with a patch on his knee holds an effigy of Christ. The patch alludes to

Catholics kneeling in prayer and to the act of sublimation, showing that religion often

keeps you on your knees.

- The female figure with her throat being sliced and the crying baby suggest that the

casualties of war are often innocent women and children.

- This hummingbird is Huitzilopochtli, the Aztec god of war and simultaneously god of the

sun. Huitzilopochtli rests between a death figure wielding an AK-47, representing war,

and a Madonna-esque woman who, like the sun, enables life. The cycle of life contains

both death, as caused by war, and rebirth.

- This creature – half animal, half man – signifies the brutality of war. A reference to

Dante’s Inferno, the Minotaur guards the seventh circle of Hell where purveyors of

violence are punished. The Minotaur prevents Dante and Virgil’s entrance, but Virgil

taunts the Minotaur, causing it to react in bestial rage – a distraction that allows Dante

and Virgil to pass.

- The tumbling woman symbolizes the incidental causes of death such as freak accidents,

car accidents – the unpreventable death. Her blood-smeared face is contrasted with the

mask beside her, which suggests the destruction of beauty.

- The monkey mask is a reference to Ozomatli, the Aztec monkey who was associated

with the god of music and dance; he is identified with the arts, games and fun. This

creature emphasizes the celebratory aspect of the Death March.

- A delicate female face represents the beauty of life, and is juxtaposed against the face

of a dead man that holds her. The youthful Madonna is caressed by age, showing that

youth and beauty are ephemeral.

- In Haitian Voodoo rituals, the blood of a decapitated rooster is the gods’ favorite

offering, but this sacrifice is said to lead to premature death.

- A corpse in a tagged body bag is ready to ascend to the heavens, but is held down by a

man holding a skull, trapping her spirit in a state of limbo between life and death.

- A self-portrait shows that the artist too is marching towards death; even he is not

exempt from man’s common fate.

- This woman holds her hands in the gesture of a puppeteer, yet she has neither strings

nor puppets to manipulate. This empty gesture shows it is impossible for life to control

death.

- A death figure carrying a portrait of himself nears the end of the death procession.

Beneath him are those who were lost in the parade, victims of the Death March

stampede.

- These stylized limbs, a reference to Picasso’s Guernica, conclude the Death March.

We come into this life with a big bang, but we leave as nothing but bones, devoid of

corporeality.